As Minnesota public health officials faced the worst health crisis in the state’s history, they were doing so with less funding than a decade ago, a new analysis shows.

Public health spending in Minnesota dropped about 9% between 2010 and 2018, according to data reviewed by the Associated Press, Kaiser Health News and KARE 11.

“That is of deep concern,” said Health Commissioner Jan Malcolm. “The reduction in funding has meant that we’ve had to really become very spread thin over a wide, wide range of issues.”

Still, Minnesota’s funding levels have fared better than the national average and some neighboring states. Since 2010, average spending for state public health departments has dropped by 16% per capita and spending for local health departments has fallen by 18% nationwide, the analysis shows.

At least 38,000 state and local public health jobs have disappeared across the country since the 2008 recession, leaving a skeletal workforce for what was once viewed as one of the world’s top public health systems, the analysis found.

Robert Redfield, the director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, said in an interview in April that his “biggest regret” was “that our nation failed over decades to effectively invest in public health.”

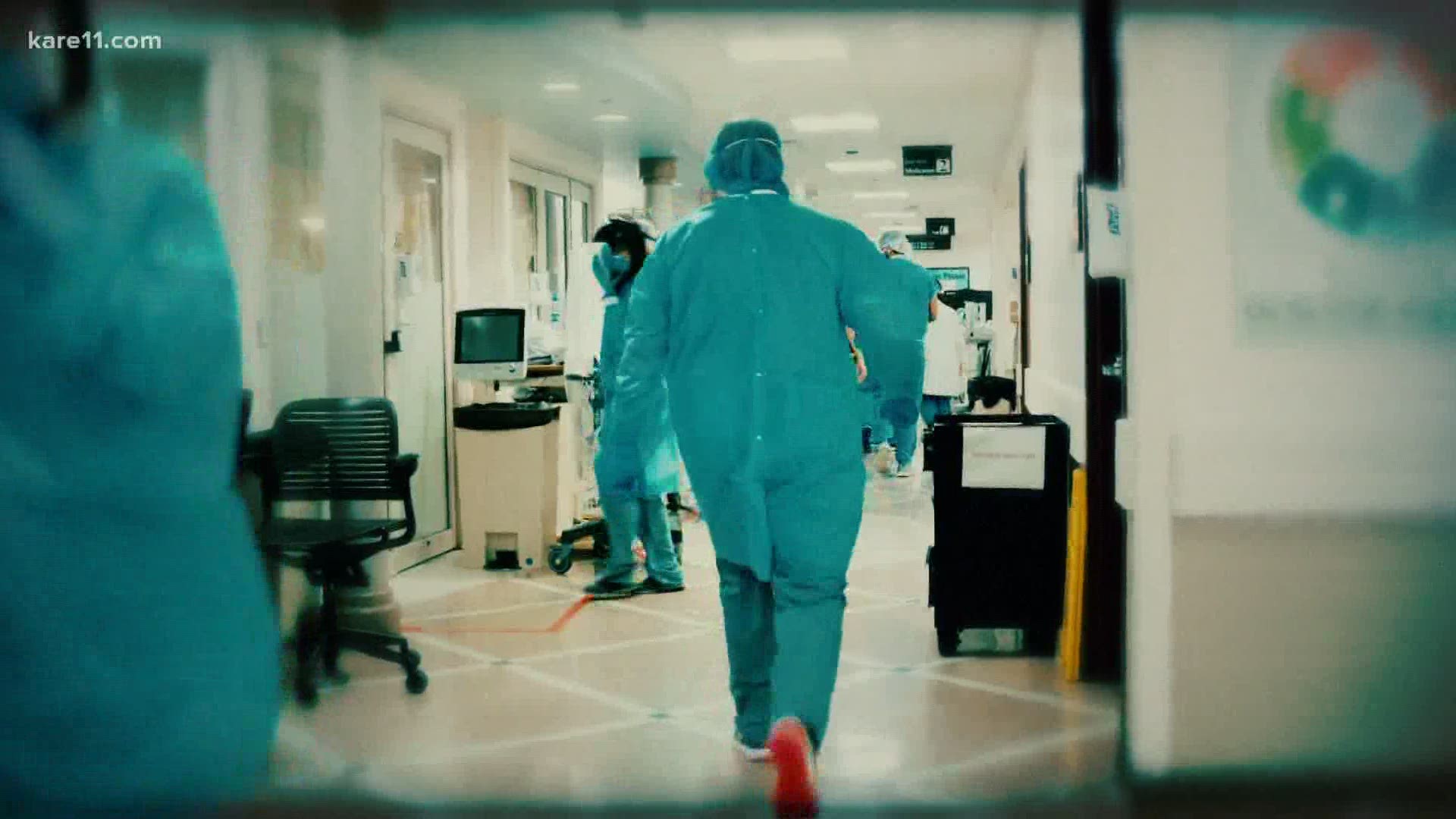

So, when the COVID-19 outbreak arrived — and when, according to some public health experts, the federal government bungled its response — hollowed-out state and local health departments were ill-equipped to step into the breach.

Had Minnesota’s public health agencies been better funded at the start of the outbreak, Health Commissioner Malcolm believes there could have been better outcomes early on.

“I think we would have been able to more quickly be able to identify hotspots where the epidemic was growing more quickly and been able to intervene more quickly,” Malcolm said.

‘Invisible’ work

Much of the work public health departments do is unheralded and often behind the scenes. Just some of their duties: prevent disease outbreaks and provide vaccines, inspect restaurants for food safety and help administer food and nutrition programs for people living in poverty.

“Public health loves to say: When we do our job, nothing happens. But that’s not really a great badge,” said Scott Becker, chief executive officer of the Association of Public Health Laboratories. “We test 97% of America’s babies for metabolic or other disorders. We do the water testing. You like to swim in the lake and you don’t like poop in there? Think of us.”

But the public doesn’t see the disasters they thwart. “And it’s easy to neglect the invisible,” Becker said.

Staffing and resources for Minnesota’s local public health departments were already stretched thin before the pandemic. A 2017 report to the legislature found that numerous departments said they felt ill-equipped at the time to handle even a small disease outbreak – especially in rural areas, where the report noted that communities tend to be poorer and have worse health outcomes.

One director of a small department said that if a tuberculosis outbreak were to occur, for example, the agency would “have no capacity to manage (it).”

“My staff are all at or over capacity,” the manager said at the time.

A follow-up survey that year found that the “majority of Minnesota’s local health departments reported they could not carry out several core activities.”

A KARE 11 analysis found nine of the 10 largest percentage declines in public health budgets between 2013 and 2018 occurred outside the Twin Cities metro area. The lone exception was Edina, where city officials say the Health Department budget showed a change because some functions had been transferred to other departments.

Since then, public health staffing and funding have only gotten worse, said Kathleen Norlein, the president-elect of the Minnesota Public Health Association.

When the coronavirus hit, Norlein said agencies dedicated nearly all of their resources to responding to the pandemic, putting other crucial functions aside.

“Public health is really prevention of problems,” she said. “We don’t know yet what we’ll see.”

There are already early warning signs, said Scott Smith, a Minnesota Health Department spokesman. Among them: Suicides and overdoses are rising, domestic abuse centers say they have more calls, people with chronic uncontrolled conditions like diabetes and hypertension are not following through on their care, Smith said.

The department is also concerned that falling rates of childhood immunizations during the COVID crisis could lead to other disease outbreaks later.

“In all of these cases, staff working on these issues have been diverted,” Smith said.

Health staffing

Only about 2% of state spending in Minnesota goes toward public health – or about $104 spent per person. That’s lower than the two Dakotas, higher than Wisconsin and Iowa, and ranks in the middle nationwide.

While the Associated Press and Kaiser Health data showed funding cuts have eliminated thousands of public health jobs across the country, the same data shows overall staffing levels have remained steady in Minnesota since 2010.

But some frontline agencies have been forced to make cuts.

Funding cuts primarily impact staffing, said Jonelle Hubbard, Anoka County’s Public Health Director, where data shows they’ve seen a 16% loss in full-time staff since 2013.

“We’ve seen a reduction in funding, but haven’t seen a reduction in requirements from the state,” Hubbard said.

Public health staffing cuts have not been felt equally across the state, the data show. Some counties have seen anywhere from half to three-quarters of their staff cut, while others have seen increases.

Minneapolis is an example of a large agency that has increased public health spending. Support from the mayor and city council allowed the city’s public health department to keep its staffing levels about the same since 2013 and increase its spending by about 22 percent.

The result? Noya Woodrich, the deputy commissioner for the city’s health department, said the agency has been better prepared to handle COVID and has the resources to do the necessary contact tracing, while also dealing with other public health concerns after the death of George Floyd and subsequent protests.

“We are having an impact across the board. It’s not easy to see, but it’s definitely there,” she said.

In Kanabec County in Central Minnesota, the agency fights for grants to provide services and increase funding, said Community Health Director Kathy Burski. Yet despite being able to spend more on public health, they’ve had to cut staffing.

Responding to COVID-19 and providing essential services like food to those in quarantine takes top priority, often at the expense of other core responsibilities.

“You’re robbing Peter to pay Paul,” Burski said.