MINNEAPOLIS - From the moment Paisleigh and Paislyn Martinez entered the world together, on February 10, 2017, six weeks early, their twin bond was immediate.

The identical twin girls reached out and touched each other’s faces in the University of Minnesota Masonic Children’s Hospital Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU). They held each other’s pacifiers. Their hearts beat in near unison.

“It was a miracle, it really was,” said Paris Bryan, their mother.

But for Bryan and her fiancé, Ernesto Martinez, of Cass Lake, Minnesota, the biggest surprise was yet to come.

CONJOINED, HEARTS CONNECTED

Around three months into Bryan’s pregnancy, an ultrasound revealed her twin girls were conjoined, from chest to their abdomen, connected at the chest, heart and liver.

Conjoined twins occur approximately in one of 200,000 live births -- and depending on how they're conjoined -- up to one in a million births, according to University of Minnesota physicians, who diagnosed Paisleigh and Paislyn as thoraco-omphalopagus conjoined twins.

Conjoined twins with a connection between the heart faced the highest risk of death. The twins lacked a breastbone, and their livers were fused in the middle.

Dr. Thomas George, University of Minnesota Masonic Children’s Hospital neonatologist, said he had only seen conjoined twins once in his 25 years in medicine, and in that case, the twins did not survive.

“But this was an extraordinary experience, to see these girls come out, what was amazing too, they clearly already had a relationship with each other, they reached out and touched each other,” said Dr. George.

Doctors discovered Paislyn had a congenital heart defect, one of the most severe heart deformities possible, with one ventricle in her heart instead of two ventricles. Her condition is known as tricuspid atresia with transposition of the great vessels—made Paislyn’s heart too weak to pump blood on its own.

“It was extraordinarily shocking. We had many different conversations with Paris and Ernesto, we informed them that number one, we could lose one or both twins,” said Dr. Daniel Saltzman, University of Minnesota Masonic Children’s Hospital pediatric surgeon.

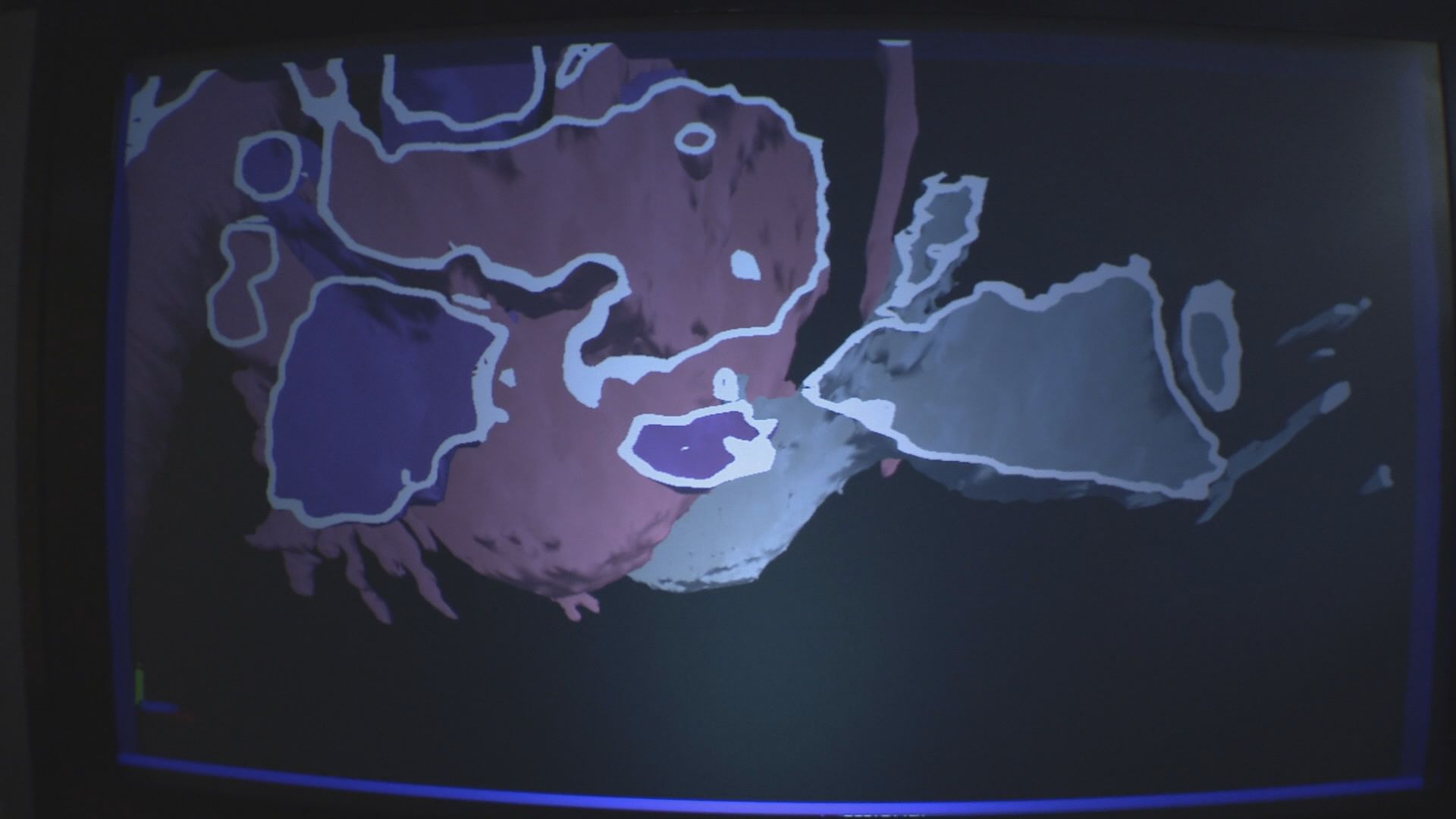

At first, doctors believed their hearts were separate, but touching one another, but once doctors turned to breakthrough 3D technology, pioneered at the University of Minnesota, and used at only a handful of places in the world, they explored a new revelation.

A team of University of Minnesota Masonic Children’s Hospital doctors then spent months planning and performing a groundbreaking delivery and separation of the conjoined twins, using 3D printing and imaging technology to discover how the baby girls’ hearts were intricately connected.

A wide range of physician specialists spent months studying the twins, and orchestrated elaborate simulations of how they would deliver the twins, and separate them when the babies grew stronger to withstand surgery.

SEEING TWINS IN A THIRD DIMENSION

To get a better idea of how the twins were conjoined, Dr. Saltzman’s team worked with the University of Minnesota Medical Devices Center to create a 3-D reconstruction of the babies’ hearts. A 3D printed heart model – expanded in virtual reality – allowed doctors to “walk” inside the heart, showing them what they couldn’t see before, an actual connection, or “bridge,” from one heart to the other.

“It felt like the future of medicine, it was really exciting,” said Dr. Matthew Ambrose, University of Minnesota Masonic Children’s pediatric cardiologist. “It was an amazing experience to go over and in three dimension, it was something we had to construct in our heads only up until that time.”

The 3D imaging changed the surgical plan and changed how doctors would make an incision into their connected hearts. The technology also helped doctors understand another discovery, Paisleigh was acting as a heart, lung and dialysis machine for Paislyn, keeping her sister alive.

“She was doing everything for her sister to make sure she was okay, it was amazing,” said Bryan.

MORE HEART COMPLICATIONS

While doctors hoped to perform a separation surgery when the twins reached six months of age, it soon became apparent Paislyn’s heart condition would threaten both of their lives.

“The problem with Paislyn’s heart would have been life limiting for both of them, without separation, Paislyn would slowly succumb to that and take her twin with her,” said Dr. Ambrose.

Less than a week before the scheduled separation surgery, Paislyn grew very ill. If she was going to going to survive the surgery, the medical staff had to act quickly.

“It’s the one operation we will do that has a 200 percent mortality, or 200 percent chance of risk of death,” said Dr. Saltzman.

Surgeons created a needed hole between the upper chambers of Paislyn’s heart using what is known as transcatheter intervention techniques—another a groundbreaking procedure, because never before had this kind of surgery been performed on a set of conjoined twins, according to Dr. Gurumurthy Hiremath, a pediatric cardiologist who performed the procedure.

Dr. Hiremath used a balloon catheter, navigating through her heart, and essentially ripping a large hole between the two upper chambers to stabilize Paislyn’s heart for surgery, as the twins were now days from separation

SEPARATION DAY

On May 25, 2017, a team of more than 40 people filled the operating room in the early morning hours.

Bryan and Martinez barely slept, worried about their baby girls’ survival.

“It was the most terrifying journey ever. Seeing them leave the room, that scared the crap out of me because didn’t know if I would be seeing them again, or just seeing one of them,” said Martinez, through tears. “That was probably the scariest thing of my life, right there.”

What they didn’t know, after months of research and rehearsal, the team of doctors were confident the separation would be successful.

“We were psyched. I didn’t sleep the night before I was so excited,” said Dr. Saltzman.

The operating room divided into two teams, half wearing blue hats for one baby, red hats for the other baby. They tracked details down to their tiny toes, painting one baby girl with blue toenail polish, and then other with pink to properly identify each twin.

“It was a surreal experience, everyone working in harmony and concert, it was one of the greatest moments of my surgical career to be honest with you,” said Dr. Saltzman.

Surgeons first separated the chest wall and fused livers. Then, Dr. Anthony Azakie, head of pediatric cardiothoracic surgery at the University of Minnesota, made the final incision, delicately separating the baby girl’s linked hearts.

“Paislyn and Paisleigh’s mom showed a tremendous amount of maturity and understanding and in some ways, she was very supportive and comforting, while we were trying to support and comfort her,” said Dr. Azakie. “After having done thousands of operations I think about that incredible trust parents have handing their babies over to us, it continues to move me.”

The operating room filled with applause and tears when the girls were finally separated, as Paisleigh was wheeled to recovery, and Paislyn stayed in the operating room for a subsequent surgery to repair an artery in her heart.

An estimated 15-hour separation surgery was completed in nine hours.

“The euphoria after separation was palpable. People were on top of the world because we had done something really, really amazing,” said Dr. Saltzman.

University of Minnesota doctors believe the 3D modeling and imaging used to see the twins’ connected hearts now has many other applications and will be used in medical journals, and future cases beyond understanding conjoined twins.

“THEY’RE NOT DONE FIGHTING”

Today, the twins recover in separate rooms, both still need breathing support and have a significant amount of healing still needed from their major chest incisions.

“They are not done fighting, they are not. They still have a long road,” said Paris Bryan, standing over her daughter Paisleigh, watching her chest rise and fall quickly, breathing heavily.

“She still tries, after the separation, she still tries to work for Paislyn. She still breathes too fast, she’s still tries to work for another body, but she’s not there,” said Bryan.

Each girl has a photo of her twin above her bed, and sleeps with a stuffed bunny with the other’s scent on it. They have been reunited once, and when the girls are upset, the care teams have placed mirrors in front of each baby to calm them, mimicking what they have always known.

“It looks like they are looking at their sister but they are really looking at themselves. It’s so heartbreaking, it’s unreal, it really still is,” said Bryan.

Paislyn will need several more heart surgeries ahead and has faced more critical ups and downs since separation. The babies will be hospitalized up to four or five more months, and when they go home will have continued complex care, each needing to wear what doctors describe as “turtle shells” or protective gear to protect their hearts since they lack a breast bone.

“In our culture, they always say they only give you as much as you can handle, that’s where girls come in. They knew we could make it through and we did,” said Bryan, gaining strength from her family’s heritage on the Leech Lake Band of Ojibwe.

Her family now holds tight to dreams for the lives than began in unison, those twin hearts with a connection that will always be one-of-a-kind.

“It made me appreciate my kids’ life even more. Knowing we could lost one of them, it makes me cherish the time more than ever,” said Martinez. “Every moment counts.”

Bryan and Martinez have several older children. A fundraising page has been created to support the family’s medical bills and lost wages, since they’ve needed to relocate to the Twin Cities for care, living at the Minneapolis Ronald McDonald House at the University of Minnesota campus since February.