LONG PRAIRIE, Minn. — One of the worst moments of Brett Huber, Jr.’s young life went viral.

In March 2017, video taken by a nearby driver showed the 25-year-old high on drugs and in the midst of a mental health crisis on Interstate 94 in Minnesota. He had stolen two cars, crashed them both, then climbed atop a semi-truck, took off his shirt and howled at passing traffic.

Only a few days before, Huber was a U. S. Senate aide working in Washington, D.C.

“He was obviously not the same kid,” said his father, Brett Huber, Sr.

After his arrest, Brett would spend the next three months in the Todd County jail. His family thought he’d be safe there – until he could get the help he needed.

They were wrong.

What happened to Brett Huber in jail would prompt a federal lawsuit – one of an unprecedented and growing number of death lawsuits that a KARE 11 investigation has found cost Minnesota taxpayers more than $10 million over the past decade. And taxpayers may soon be on the hook for a lot more.

Warning signs for weeks

There would be repeated warnings that Brett was mentally unstable and possibly suicidal. On March 21, he asked a jailer, “Why don’t you guys just let me kill myself right now?” Another day, guards reported he tried to tie a shirt around his neck and made suicidal comments.

More than a month later he was still having hallucinations. A jail nurse noted Brett is “seeing things crawling in the hallways.”

Seven weeks after his arrest, Brett was taken to CentraCare Health Clinic where a nurse practitioner diagnosed him with a “severe episode of recurrent major depressive disorder, with psychotic features.” She prescribed an antipsychotic drug and noted he would “likely benefit from a full psychiatric evaluation.”

That mental health evaluation never happened, according a federal lawsuit filed later by his family.

Finally, on June 9, in full view of a jail video camera, Brett is seen spending several minutes twirling his sheet into a noose, then wrapping it around his neck.

“He was denied the type of treatment he needed. And now I no longer have a son,” his father said.

In December 2018, four months after the lawsuit was filed, Todd County settled with the family for $1.8 million.

The federal complaint listed a litany of failures. The Minnesota Department of Corrections (DOC) found that jail staff falsified records by logging well-being checks that were not done. One of the false entries was at the same time Brett Huber was hanging himself.

“I knew of no other way to try to have an impact on the system,” said Brett Huber, Sr., of the lawsuit. “If you can’t find any other avenue to expose their actions … the only way you can get their attention is through their pocketbooks.”

Costly jail death lawsuits

Jail failures across Minnesota are costing both lives and money.

In the last 10 years, Minnesota counties have paid out more than $10 million in settlements and legal fees following lawsuits accusing jails of providing inadequate to non-existent health care to inmates.

KARE 11 has identified 56 inmate deaths in Minnesota since 2015 in jails, which generally hold people who are presumed innocent, charged with crimes and awaiting trials. Others are serving short sentences of less than a year.

Fifteen of those deaths have resulted in active or soon-to-be filed federal lawsuits, a record number, according to court files and interviews.

Each of those cases are backed by private attorneys seeking millions for the clients, saying they have mountains of evidence to support their claims that the jails failed to keep their inmates alive.

Some of those cases have already been profiled by KARE 11, including:

- Hardel Sherrell, who became paralyzed and died in 2018, while in the Beltrami County jail,

- James Lynas, who despite indications that he was suicidal, did not receive mental health care and hung himself in the Sherburne County jail in 2017.

“I think it’s because a lot of counties made it their primary goal to try to do things (provide health care) cheaper than they were doing them before,” said Andy Noel, an attorney who has brought several lawsuits against jails, including the Huber case. “This is one area where there are literally lives at stake and you can’t do it on the cheap.”

Bill Hutton, executive director of the Minnesota Sheriffs’ Association, points to another reason for the increase in lawsuits. The number of mentally ill jail inmates continues to proliferate, he said, many of whom should instead be getting treatment in hospital settings.

Jails are required to provide those inmates with mental health care, something they were never equipped to do, Hutton said. Providing inmates with appropriate care means spending more money on medicine, personnel and training, stretching budgets.

“The last thing a sheriff wants is for anybody to die in custody,” Hutton said. “But not everything can go right.”

Minnesota jail suicides

In Minnesota, too often it’s going wrong, particularly when it comes to suicidal inmates.

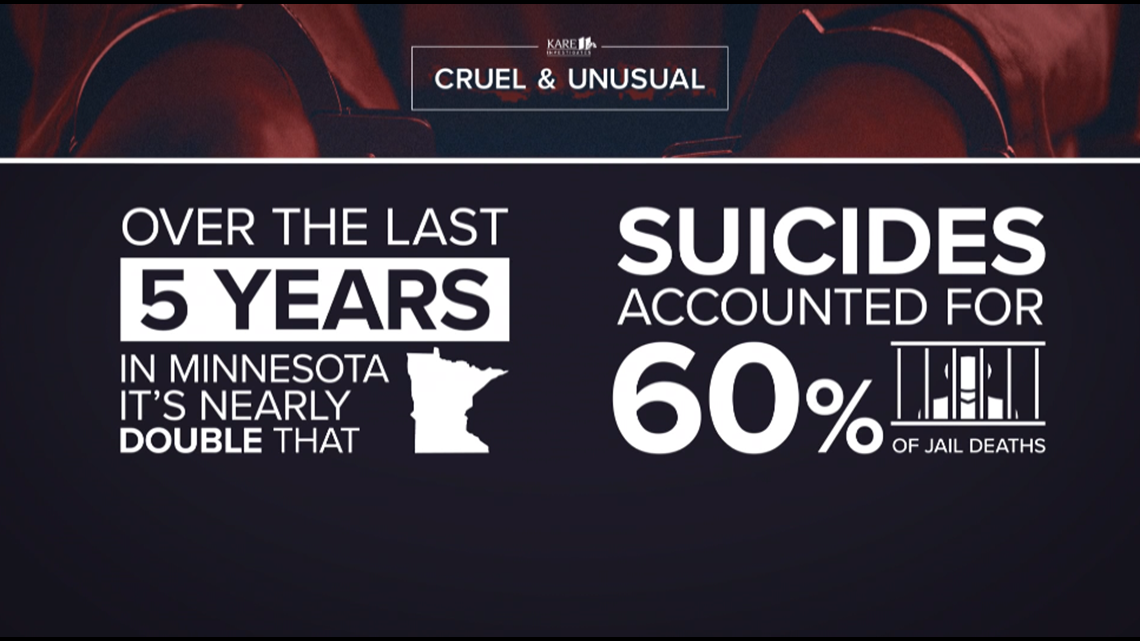

According to federal data from the Office of Justice Programs (OJP), nationally, suicides account for 31% of jail deaths.

However, over the last five years, KARE 11’s analysis discovered suicides accounted for 60 % of deaths in Minnesota jails – nearly double the national average.

KARE 11 presented that finding to DOC Commissioner Paul Schnell.

“It tells me, as a whole, we need to do a whole lot better at assessing suicidal ideation and risk, and then aggressively taking action to make sure we are providing the level of care and oversight and intervention necessary to prevent suicidal actions,” Schnell said.

Constitutional duty

One of the ironies of the U.S. health care system is while the general public is not guaranteed care, that changes once a person is incarcerated.

Deprived of their freedom, inmates must depend on the government to care for them.

“There is a special relationship that exists between the parties,” said Bradley Colbert, a professor at the Mitchell Hamline School of Law. “If the government is going to deprive you of things, then they have a duty to protect you from harm.”

The Supreme Court has ruled that failure to provide that care can be a violation of the Eighth Amendment ban on cruel and unusual punishment, but only if inmates can prove “deliberate indifference” to their medical needs.

“These are hard cases to win,” said David Schultz, a political science and legal professor at Hamline University. “It’s not just showing negligence. You have to show they deliberately chose not to care.”

For suicidal inmates, it means not only must the government provide mental health care, but also take steps to ensure the inmate doesn’t commit suicide.

The largest jail death settlements in Minnesota have resulted from such cases. In Cass County in 2018, for example, an inmate who was known to be suicidal and mentally ill was still able to drink about two cups of toxic windshield wiper fluid.

Though the guards knew he had ingested the poison, he was never taken to a doctor, according to the complaint in the case. Instead he was left in his cell, where he died about 15 hours later.

Cass County settled with the man’s family for $2 million before the case could even officially be filed in federal court.

It typically takes lawsuits to uncover failures like the ones discovered in the Cass County case.

As KARE 11 has reported, most counties fail to follow national best practice guidelines about reviewing medical care after a jail death. Those reviews are meant to discover what may have gone wrong in a case to ensure that the mistakes never happen again.

The state Department of Corrections licenses county jails and reviews jail deaths. But KARE 11 has documented repeated cases in which the DOC review missed failures that led to inmate deaths.

It would take a lawsuit to reveal what really happened to Brett Huber, Jr.

A father’s search for the truth

Even as Brett’s mental health deteriorated, his father said jailers assured his family that his son was safe, acting normally and getting treatment for his mental health.

Then he learned the truth.

“I can’t make up a worse horror story,” Brett’s father told KARE 11. “If I sat down and said, ‘How do I ruin a parent’s life? What could I do to their child?’ I couldn’t have come up with anything this traumatic.”

His son seemingly had it all. Growing up in Spearfish, S.D, gifted with what his father describes as a genius level IQ, he was the type of kid who breezed through school, never feeling challenged as he got straight A’s. He volunteered at non-profits and was active in his church.

And there were his physical gifts. Handsome, tall, and 180-pounds of “pure muscle,” as his father says, he was a varsity wrestler in middle school. At age 11, he was certified as a master scuba diver.

But what he truly wanted, he could never obtain.

“More than anything else, he wanted freedom from his addiction,” his father said. He believes Brett turned to drugs as a way to fit in, with ecstasy becoming his drug of choice.

In March 2017, realizing he needed to get his use under control, he left his job in the Senate. His father says he planned to go to visit his grandparents in southwest Minnesota before enrolling in a treatment program. But he first made a stop at an ex-girlfriend’s house in the Twin Cities.

That’s when he apparently went on a bender.

High on drugs

According to a police report, Brett showed up at an Alexandria hospital emergency room saying he was high on ecstasy. Staff there planned to take him to detox. But instead he ran, stole a car, drove it into a pond, then stole another car that he crashed on I-94.

The video later posted to Facebook captured him standing atop the semi-truck.

Brett was arrested and taken back to the hospital, where he was delusional – worrying that officers were going to “chop him up.”

Instead of being taken for mental health treatment for evaluation, an hour later court records show he was booked into the Todd County jail.

In jail, his mental health would swing wildly, switching from manic to depressive to delusional to suicidal, according to the federal lawsuit.

At one point, records show he refused a guard’s order to go back into his cell and took off running through the jail. A guard tased him, hitting him in the abdomen and dropping him to the floor.

A month later, he still hadn’t seen a mental health professional. He asked to call President Donald Trump, saying people in the jail would hurt him if he could not use the phone.

He took off running again. Guards, again, chased him down and locked him in a cell. There, he tried to drown himself by plugging his nose and pouring water into his mouth from the sink.

His family said they were never told about any of that, despite repeatedly asking about his well-being.

His father took a leave of absence from his job in Alaska so he could visit his son in jail.

Some days his son was rational and like his normal self, his father said. Other times it looked like he hadn’t showered for weeks, was wild-eyed or cried through entire visits.

‘He’s being cared for’

His family says they could have easily bailed him out, but instead chose to keep him in the jail – believing that was the safest place for him. They wanted to wait for a court-ordered evaluation of his mental health, routine in cases like his.

That evaluation never happened. It was scheduled for June 15, but he died before it could take place.

After each visit, Huber Sr. said he would bring concerns about his son’s well-being to the jail administrator Scott Wright or any other senior leadership there. When he couldn’t visit, he said he repeatedly called Wright to ask about his son.

The response was the same, he said: Don’t worry. He’s being cared for.

“I was led to believe he was in a good facility, that he was being monitored, that they were doing their job, that he wasn’t having issues, and that the court ordered evaluation would begin soon,” he said.

As a public servant himself – he has served as a policy and communications advisor to Alaska’s governor – Brett’s father says he believed them.

“If they would have ever told me the truth, I would have bailed him out that day,” he said.

His father remembers that during his last visit with his son in June, he was crying.

“I feel like quitting,” he told his father.

Although Brett Sr. says he shared his concerns with the jail administrator Scott Wright, he claims he was told again that everything was fine.

Wright, who is still the jail’s administrator, did not respond to an interview request for this story.

“There’s been an incident”

Two days later, despite his months of delusions and depression and his suicide attempt, Brett was left in a cell alone with a bed sheet.

Despite the cell having 24-hour surveillance video, no guard noticed as he twisted the sheet into a noose for several minutes – then hanged himself from a bed post.

Jail video shows ten minutes passed before a guard entered the cell and saw what happened.

Brett’s father says he was driving to Alaska when jail administrator Wright called him. “There’s been an incident with your son,” Huber Sr., said he was told.

“Can you tell me more?” he pleaded.

“That’s all I can tell you.”

Brett’s father said he hopped on a plane and returned to Minnesota. By that time his wife was able to find out that Brett was at a St. Cloud hospital – after hanging himself and being without oxygen for several minutes.

On the way to the hospital, his father held out hope that his son could recover. But before he could enter his son’s room, he said a Todd County sheriff’s deputy posted at the door stopped him from going through until he could prove he was Brett’s father.

“The only time someone watched him for 24 hours,” his father said.

There was nothing that could be done. His son was brain dead. Two days after hanging himself, Brett was taken off the ventilator. His parents held his hands as he died.

Lawsuit reveals past problems at the jail

Hoping to learn what happened to his son, Brett’s father said he requested all of his son’s records from Todd County, but never got a response.

His lawyer, Andy Noel, was able to acquire the records as part of the discovery process in the lawsuit, including jail logs and surveillance video.

Only then did the Huber family learn what happened to their son during his time at the jail. For the first time they discovered that their son had been tased, repeatedly told guards that he heard voices and had tried to commit suicide. Despite that, he was never treated by a mental health professional.

But there was more. The lawsuit also revealed that the jail had a history of problems, including being cited by the state for lack of adequate staffing and staff training on suicide risk and precautions.

Records show the state had also cited the jail for failing to conduct required well-being checks on inmates. In some cases, guards had falsified logs to show that they had checked on inmates when they never did, including the death of another inmate just one month before Brett.

When state inspectors reviewed records from the day Brett hanged himself, they discovered guards had falsified three well-being checks that never happened, including once when video showed he was already hanging from the bed sheet.

Three years later, Brett’s father says the pain will never go away. He doesn’t want it to.

“That pain is a piece of my son that I still have,” he said.

That also drives him to tell his son’s story, in hopes that what happened to him never happens to anyone else.

“Brett was a great kid, and if I can do something in his honor, I will,” he said.

“Whatever the good people of Minnesota can do to say, ‘This is an outrage and it needs to change.’ I beg you to do that.”

If you have a tip about something KARE 11 should investigate, please contact us at: investigations@kare11.com