KARE 11 Investigates: Juvenile lockups routinely order kids into solitary confinement

Controversial practice puts kids' mental health and the public’s safety at risk, experts say. One teen who got out: "I didn’t know right from wrong."

Emitt Long grew up choked, burned, and beaten. He suffered from depression and was harming himself as early as age 6.

He began acting out. As he grew into a teenager, he committed felony crimes that put him into Minnesota’s juvenile justice system, which is supposed to help rehabilitate kids like Emitt while protecting the public.

His crimes were so serious that at age 14, he was sent to the Red Wing juvenile prison. There, records show he would be repeatedly placed into what’s known as “Disciplinary Room Time” – where kids are locked alone in their cells as punishment.

“In Minnesota, we refer to solitary confinement as Disciplinary Room Time, or DRT,” a Department of Corrections official testified to the state legislature in 2021.

Emitt is one of thousands of kids who have been ordered into solitary confinement in Minnesota’s juvenile lockups, a KARE 11 Investigation has found, a practice that experts say harms youth and puts the public’s safety at risk.

“You sit in that cell for 22 hours a day and you come out for your little break,” Emitt, told KARE 11 in an interview.

He said he banged his head against the walls, pulled the dreadlocks from his hair, and begged the guards to let him out.

“They just shrugged it off and kept walking,” he said. “They treat you like a dog.”

Routinely put into solitary

KARE 11 spent months gathering and reviewing records about DRT use at Minnesota’s county-run juvenile detention centers and at the state-run Red Wing, while also reviewing state laws and licensing rules, interviewing kids who have been on the inside of the jails and reviewing their records, and talking with current and former staff who worked inside the facilities.

Among our findings:

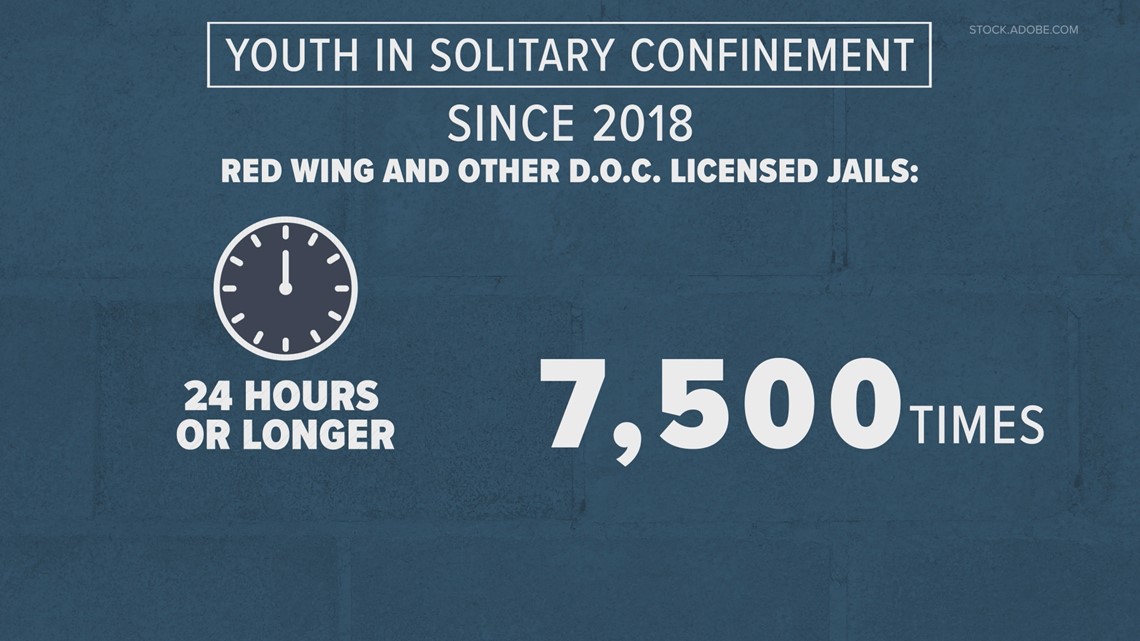

- Minnesota’s juvenile lockups have ordered kids into DRT for 24 hours or longer more than 7,500 times in the last five years – or about four times a day.

- There are few restrictions on DRT, including no limit on how long a child can be kept in solitary. Kids as young as 10 years old can be placed into solitary confinement indefinitely.

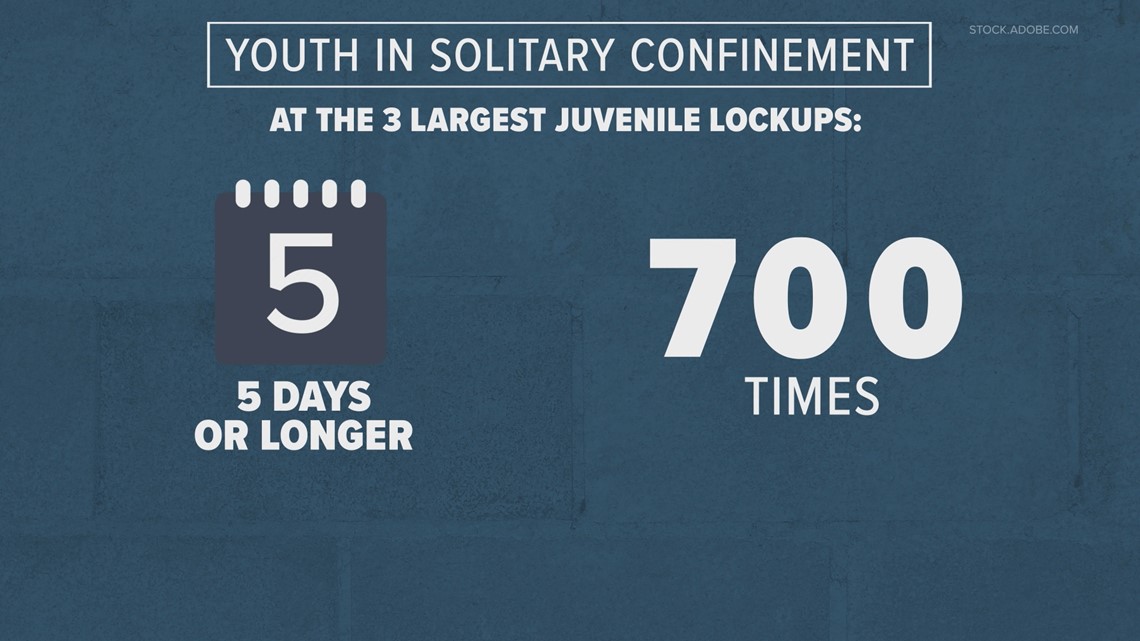

- Minnesota’s three largest juvenile lockups have ordered kids into solitary for five days or longer nearly 700 times since 2018. Records show the Hennepin County Juvenile Detention Center ordered someone in DRT for 34 days.

- There is no requirement that mentally ill children on DRT be provided any kind of mental health screenings to determine the impact of placing them into solitary confinement or specialized care – protections that would be required to be provided if they were placed in solitary in adult prisons.

(Note: You can download the data here.)

For Emitt, a catastrophic cycle began at Red Wing, where he repeatedly would be put into solitary as his violent behaviors escalated.

When he got out of Red Wing, he re-offended. His mental illness got worse. He went to juvenile detention and then back to Red Wing, where at both lockups, he spent even more time in DRT.

Released from Red Wing again, he’s now 19 and in the Hennepin County adult jail on gun possession charges.

For Emitt, solitary didn’t make him better, he said.

“It made it worse.”

'This is so damaging'

“It will make it worse” is a common refrain from mental health and criminal justice experts regarding ordering kids into solitary confinement.

Numerous national medical and correctional organizations say isolating children in emergency situations for short times is a necessary intervention. But when practices like DRT punish kids by keeping them in prolonged isolation, the impacts can be devastating.

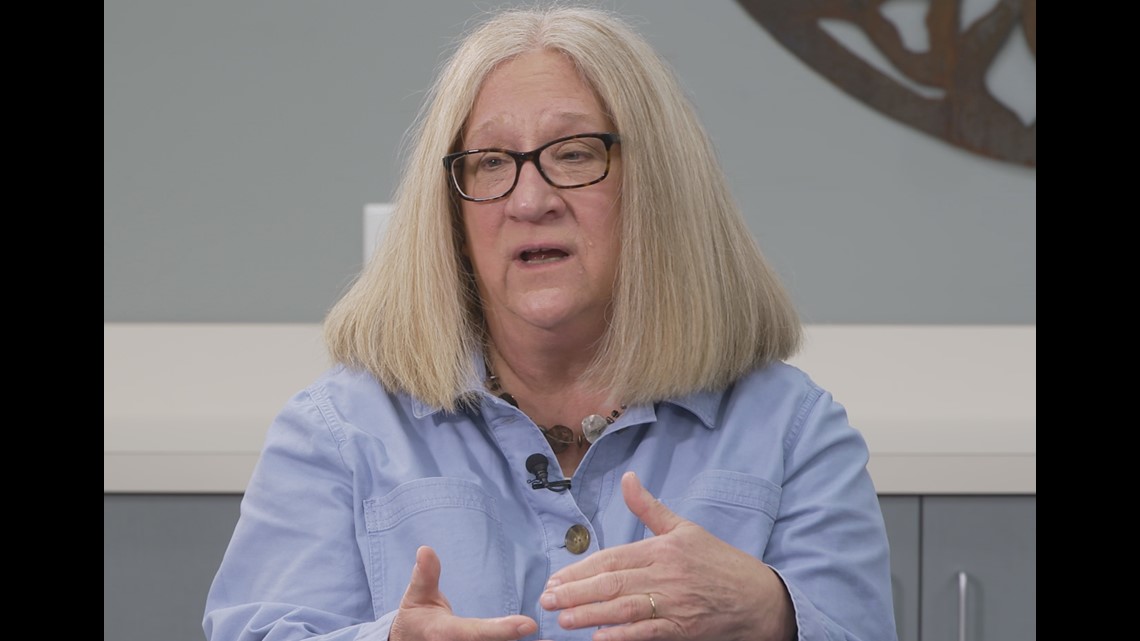

“This is so damaging to a developing brain,” said Sue Abderholden, the executive director for the National Alliance of Mental Illness in Minnesota.

Research shows that kids like Emitt who grow up abused and neglected have a biological reduction in brain chemicals that help them react appropriately to stress, explained Steven Thurber, the former clinical director of Minnesota’s child psychiatric hospital.

When those children are placed into solitary confinement, he said it can only make them more aggressive.

“It just perpetuates the problems,” Thurber said.

At a time when kids need adult mentorship and guidance the most, when locked in solitude they often think instead about how they have been wronged and attacked, said Anne Gearity, a University of Minnesota psychiatry professor and expert in child development.

“They stew and plot,” Gearity said. “We’re reinforcing what we’re trying to break.”

The vast majority of the kids in Minnesota’s juvenile lockups will get out, and go back to their homes, communities and neighborhoods.

“You’re not going to make this better,” Abderholden said. “You’re going to make things worse.”

Solitary at the juvenile prison

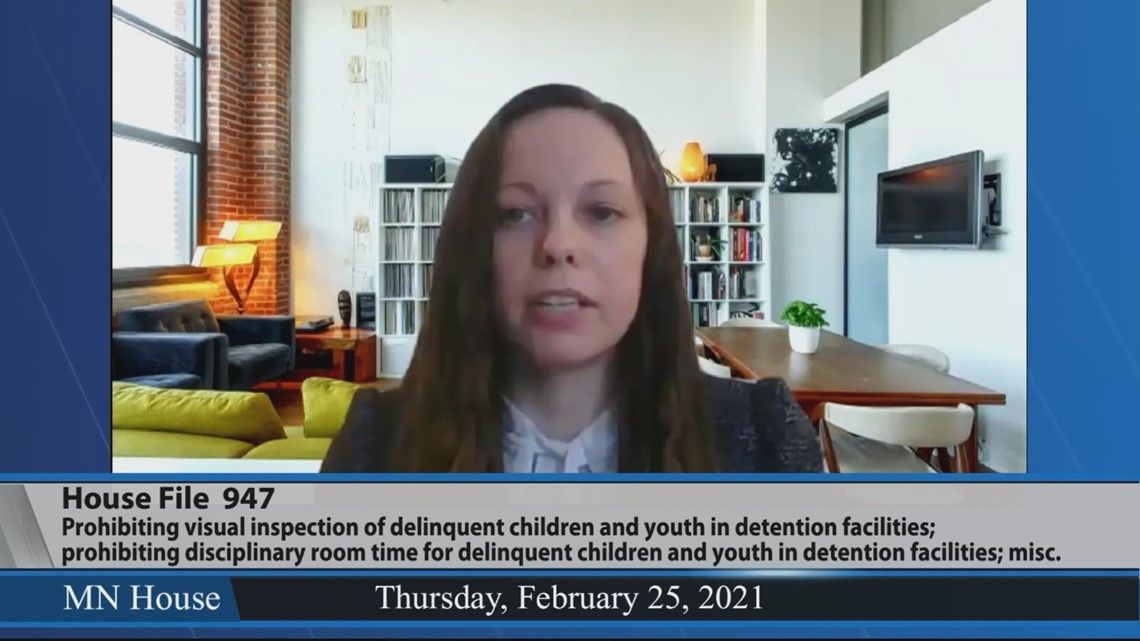

Minnesota could have done away with DRT in early 2021 when the Department of Corrections pushed a bill at the legislature to ban the practice.

“Knowing the impact on a youth’s mental health should implore us to only use isolation or seclusion when there is an imminent danger,” Katrinna Dexter, the DOC’s director of juvenile justice reform, testified to the legislature.

About half the states in the country have passed laws either banning juvenile solitary or severely restricting its use.

Minnesota’s bill gained bipartisan support, but there was pushback. The leaders of local juvenile jails sent lawmakers a letter saying, “the complete elimination of DRT will create an unsafe environment for residents, staff and visitors.”

The proposal died, and juvenile lockups continued to put kids into solitary confinement.

One of the agencies that has used DRT the most?

The Department of Corrections.

At the same time the Department was testifying in favor of the legislative ban on solitary confinement, records show the DOC routinely put kids into DRT.

In the last five years, the DOC-run Red Wing juvenile prison has ordered kids to be placed into DRT for 24 hours or more nearly 1,900 times. Records show there were more than 250 cases in which DRT was ordered for five days or more.

The average stay is around 58 hours.

DOC Commissioner Paul Schnell called the statewide use of DRT “unacceptable” when presented with KARE 11’s findings last month and vowed to reform its practice.

“I’m not going to sugarcoat it. I’m not going to defend it,” he said.

But a key lawmaker involved in the bill to ban DRT in Minnesota in 2021 says it failed in part because Schnell’s department stopped lobbying for it.

Retired State Rep. Carlos Mariani, who was chair of the House Public Safety Committee at the time, said after juvenile detention administrators pushed back against the bill, Schnell told him that the DOC would make changes to DRT by revising the licensing rules.

“That gave us permission to back off,” Mariani said.

Two years later, however, no new DRT rules have been adopted.

Schnell blamed the delay on implementing reforms at adult detention facilities.

The same year DOC originally proposed the DRT ban, lawmakers passed sweeping changes in Minnesota’s adult correctional system in the wake of KARE 11’s “Cruel and Unusual” investigation.

Schnell said the DOC still plans to eliminate DRT through licensing rules. Though isolation can still be used, he said it should not be used as punishment.

“Discipline is not on the table here,” he said. “(Seclusion) has to be used for the purposes of safety and ultimately re-engage them in programming. That’s it.”

“We have to be focused on the right interventions at the right time so that we’re all safer,” he added. “That’s what juvenile justice should be focused on.”

Is DRT grounding?

There is no universal definition of solitary confinement, particularly when it comes to juveniles. The United Nations defines solitary for adults as “the confinement of prisoners for 22 hours or more a day without meaningful human contact.”

In interviews, numerous detention center administrators have said that kids in DRT have repeated human contact, opportunities for activities and to meet with care providers, and to go to school inside the lockups -- should it be safe for them to do so.

Many of the agencies that provided data on DRT cautioned that it only showed the lengths of time youth were ordered into confinement, but not the actual time spent there.

“DRT is not solitary confinement,” James O’Donnell, the superintendent of the West Central Regional Juvenile Center, said of his detention facility in Moorhead.

O’Donnell said DRT is a crucial tool to keep detention center staff and juveniles safe.

“DRT is more synonymous with a parent grounding their child to their room. Confining a youth to their room until their behaviors can be addressed and a plan to move forward can be addressed,” he said.

O’Donnell did not provide records on individual lengths of time children spend in DRT at his facility, despite requests for the public data.

However, the data O’Donnell did provide shows that kids were kept in DRT an average of 12 to 28 hours a month since 2020.

Interviews with youth who have been inside juvenile detentions as well as current and former detention center staff statewide describe DRT as anything but “grounding.”

Noah, an 18-year-old who has been in the Hennepin Juvenile Detention Center since November 2021, told KARE 11 he’s been in DRT for up to two weeks at a time. He described being locked in his cell for 23 hours – only to be let out for physical activity.

“You don’t feel human. It’s like being in an insane asylum. It drives you crazy.,” said Noah. “All you do is just sit there and stare at the wall. And it’s just horrible.”

Last year, KARE 11 profiled a profoundly mentally ill and suicidal 16-year-old who spent days in solitary confinement at the Hennepin JDC, often only able to talk with his mother and even his social worker through a small slot meant to pass meal trays through his cell door.

At one point on DRT, he told a nurse that he felt like his cell walls were closing in on him, “making me have thoughts of killing myself.”

In a statement to KARE 11 last year, Hennepin County said: “We know the current juvenile justice system isn’t perfect, but we are committed to the safety and well-being of all youth who are under our supervision and continually look for ways to improve.”

Solitary for cell phones, cigarettes

Michael Dempsey, the executive director of the Council of Juvenile Justice Administrators, said there is a clear need to keep out-of-control kids in seclusion. He said that should be done only in emergency situations, and the youth should be returned to the general population when it is safe to do so.

Dempsey, who has served as the director of Indiana’s juvenile detention facilities, said putting kids into isolation should be rare, and they should generally spend no more than four hours there.

Seclusion should never be used as punishment, he said.

“It should only be used when a child continues to be a threat to themselves or others,” he said.

Under Minnesota’s state licensing rules, kids can be put into DRT only for what are considered “major violations.” In many detention facilities, records show kids can be ordered into DRT even if they are never a threat to staff or other kids.

In Red Wing, for example, being caught with a cell phone or cigarettes can land you in solitary for up to five days.

Kids can be ordered into DRT at the Hennepin Juvenile Detention Center for name-calling or teasing. Once there, kids can get even more time in solitary for talking to other kids through the room vents.

Kids placed on DRT in the Hennepin JDC spend an average of 48 hours there, according to county records.

“Spending 23 hours a day in isolation, that’s excessive,” Dempsey said. “There’s no reason why that should occur.”

'I didn't get that hour'

Emitt Long grew up abused in a chaotic home environment, according to court records, and experienced mental illness at a young age. At 6 years old, his mother sought help for him for depression and self-harming.

At age 12, he started running away from home. The next year he was found responsible for a misdemeanor assault and for felony terroristic threats – though court records do not provide the details for those cases. Treatment programs weren’t working.

At age 14, he was convicted of felony theft, landing him in Red Wing.

A few months into his time there, he was repeatedly put on DRT for what records described as abuse and harassment, tattooing himself and inciting others.

“I had anger issues. I had ADHD. I have mental problems,” Emitt said in his interview with KARE 11.

The solitary didn’t make him better. As the months went by, he would continue to be put into DRT. At one point, his time spent in solitary meant he couldn’t go to his aggression therapy classes.

“I was never in a regular unit because I was in segregation,” he said. “They did that (expletive) every single chance they got.”

He was supposed to get an hour outside his cell, but only if he could earn it.

“There were days where I didn’t get that hour,” he said.

He said there were times he was unable to go to the prison’s school, or if he was supposed to go, would only be there for an hour. He developed signs of bipolar disorder at Red Wing, records show.

After 18 months at the juvenile prison, he was transferred to the now-closed Hennepin Home School, which focused on rehabilitation and not restriction.

He was given appropriate mental health treatment and mentorship. He thrived. He learned to play the piano, cook and paint. He was respectful and responsible, his caseworkers would later testify, and took his job duties seriously.

He was successfully discharged after five months. Unfortunately, despite his history of mental illness, he was not provided any continuing mental health treatment, according to court records.

That’s a terrible mistake for mentally ill kids like Emitt who grew up in abusive homes, said Dr. Thurber, the child psychologist. They continue to need intensive treatment to deal with the trauma they’ve suffered and to show them appropriate behaviors – particularly if they’ve been subjected to solitary confinement.

“You can’t just cut it off cold turkey,” Thurber said.

About four months after leaving the Home School, Emitt re-offended.

Mentally ill, back in solitary

Then 16, Emitt was charged with felony burglary, stealing cars and leading police on high-speed chases. But he was so mentally ill that a judge found him unable to stand trial.

He became what is known as a “gap case,” where he was released back to the community.

He again re-offended when he jumped out of a stolen car with another teen to steal a stranger’s purse, records show. Police said the woman was stabbed during the struggle.

Hennepin County moved to prosecute Emitt as an adult. Two psychologists evaluated him, both of whom said he needed intensive mental health treatment. One felt Emitt was so ill that it should be considered a disability and needed long-term care, and perhaps needed to be hospitalized.

That never happened.

Emitt spent months at the Hennepin JDC, a facility that provides little mental health care, where records show he was repeatedly put into DRT after violent outbursts and assaults.

The judge denied Hennepin County’s attempt to try Emitt as an adult, and ordered he be put into a “rehabilitative environment.”

But the potential placement options declined to take him. Hennepin County was shutting down the Home School. With no other choice, the judge sent him back to Red Wing.

Over the span of six months there, records show he spent nearly two months combined in DRT.

“When I got out of jail I didn’t even know how to act,” Emitt said. “I didn’t know right from wrong. I couldn’t even function.”

In all, he estimates he’s spent about a year in solitary since he was 14.

In September last year, police say they found him squatting in a vacant apartment with cocaine, fentanyl and guns. Prosecutors charged him with several counts of illegally possessing firearms. Now 19 years old, if convicted, he faces a minimum sentence of five years in adult prison.

When he told his story to KARE 11, it was from the Hennepin County jail, where he appeared to be in the same cycle he had been in since age 14.

He said he had just been taken out of solitary confinement.

Watch more KARE 11 Investigates:

Watch all of the latest stories from our award-winning investigative team in our special YouTube playlist: