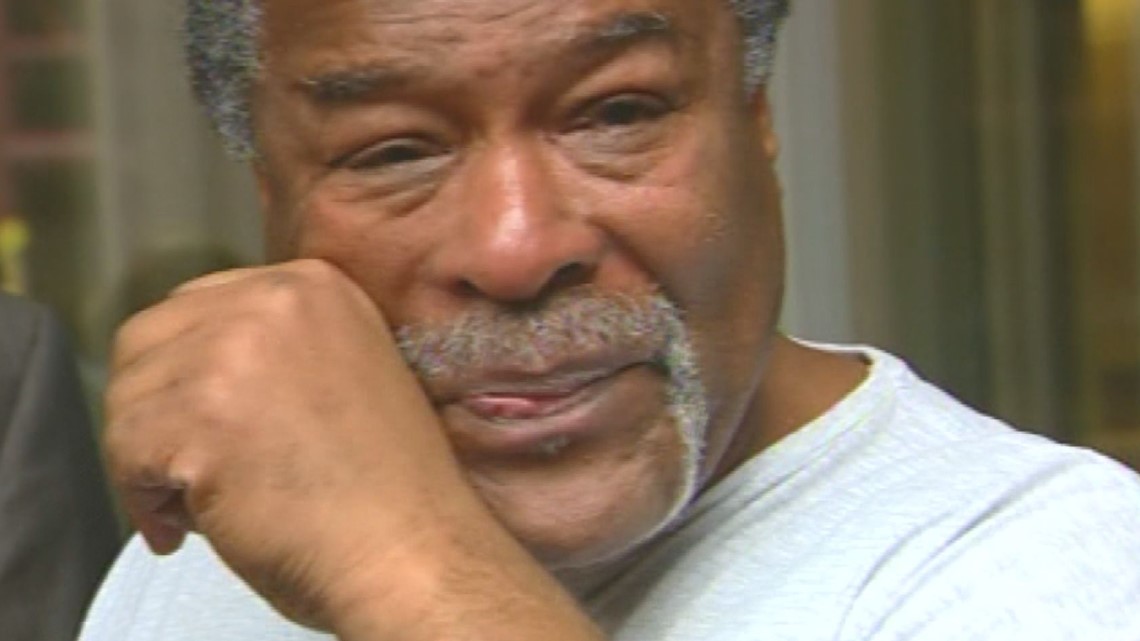

Sherman Townsend spent 10 years in prison for burglary, before another man came forward and took responsibility for the crime.

That man was the prosecution’s star witness - who said he pointed Townsend out to avoid blame for the crime.

Townsend had a hearing before a judge - and attorneys from the Great North Innocence Project presented his case. The other man, David Jones, testified on the stand that he committed the crime. He drew a map of the crime scene, and described that night in detail.

But the judge never ruled on whether Townsend deserved a new trial. Because before she could, Hennepin County Attorney Mike Freeman offered Townsend a deal. He could drop his appeal, and walk free. But he’d keep the conviction on his record.

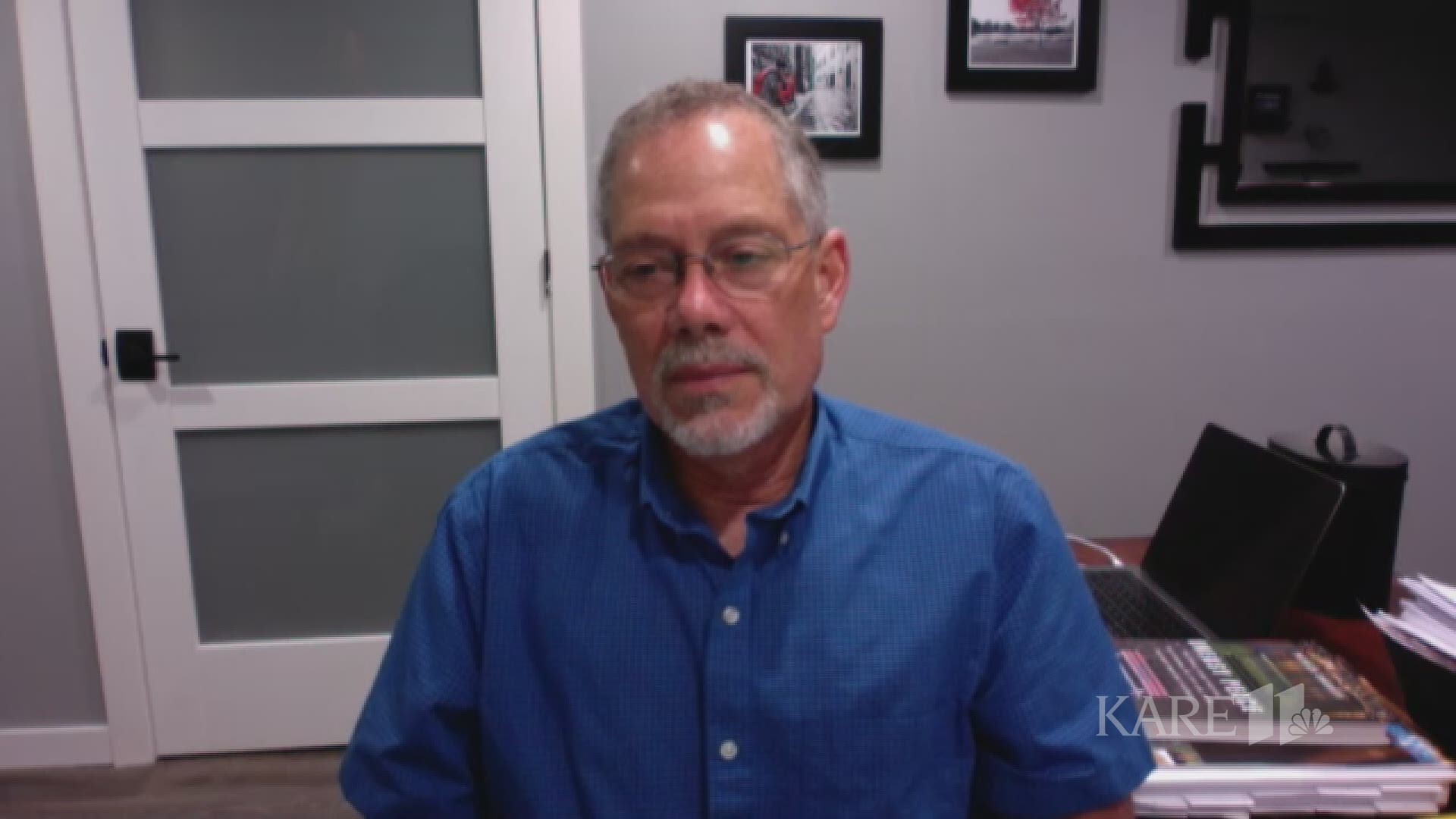

When law professor Keith Findley heard this story, he was not surprised. In fact, he found it familiar.

RELATED: After another man confessed to the crime, Hennepin County offered deal to preserve conviction

Preserving convictions

Findley co-founded the Wisconsin Innocence Project, and was the co-director for years. Now he teaches on criminal law, evidence and wrongful convictions at the University of Wisconsin Law School.

“One of the things that innocence advocates have noticed over the years is that not always, but sometimes, prosecutors, when confronted with very powerful evidence of innocence, go to great lengths to try to preserve the convictions,” Findley said. “Including making plea offers that are essentially so good that it's hard to turn them down, even for an innocent individual.”

Findley knew about deals like this anecdotally. But he wanted to know how common they were. He reached out to all of the innocence organizations in the country, asking them to provide data from all the cases they’ve litigated in the past 10 years where they have developed new evidence of innocence. He wanted to see how the prosecutors responded in those cases, if they offered deals, and what those deals looked like. He gathered 272 cases.

What Findley found was that these plea deals are not an anomaly. In fact, prosecutors offered them 64 times. That’s just under 24% of the cases. In most cases, the defendants took the deals.

“Remember, as a category, this is a group of people who already put their faith in the trial process and lost once,” Findley said. “So why would they have any faith that they would fare any better the second time, right? So you can see why these kinds of very generous plea offers, even for stone cold individuals, are going to be really, really tempting. It's going to take only the bravest, the most risk-tolerant individuals who are going to be willing to test the system a second time after having tried it and lost once already.”

Other factors can play in as well, like a person’s extenuating circumstances or family situation. Townsend, for instance, had a mother who was ill.

“One of the main things I asked God for at the beginning of prison was, ‘Please don’t let my mother die while I’m in prison,” he said. “And she ended up dying five months after I got out, so I’m glad I took the deal.”

Though nearly a quarter of the time may not seem like that much, what the data suggests is that these deals are a regular tool in a prosecutor’s toolkit. They’re a routine response to new evidence of innocence. And they are just one way a prosecutor can preserve a conviction when their case is being challenged.

Findley knows that not all of the 272 people represented in these cases are necessarily innocent. But he believes the cohort he gathered has the best chance of containing the highest number of innocent people.

“Nobody has perfect access to truth,” he said. “But what is pretty clear is that by reaching out to innocence advocacy organizations, we have the best chance of getting the best cases with the strongest claims of innocence.”

Findley said that’s because these are not your typical defense lawyers. They only offer assistance to people they believe are completely innocent.

“They are overwhelmed with requests and have very limited resources,” he said. “So their incentives are to only take those cases with the most compelling evidence of actual innocence. They screen them, they vet them, they work them thoroughly before they proceed with litigation.”

And while it’s impossible to know which people are truly innocent, Findley was correct. The cases sent to him were mostly winning claims.

When there was no plea deal reached, 86% of the defendants in all of these cases ended up successful. They had their convictions vacated, there was a finding of innocence, or the case against them was dismissed. That’s excluding cases that are still pending.

But in 62% of these same cases, prosecutors sought to preserve a conviction, at least initially - even though the data shows they were on the losing end most of the time.

On the other hand, in 34% of all the 272 cases given to Findley by nationwide innocence advocates, the prosecutors joined or did not oppose the motion. This suggests that there are also plenty of times when prosecutors recognize there is a weakness in the case, and they stop fighting to preserve that conviction.

‘Innocence problem’

Plea deals are a common fixture of the U.S. criminal justice system. The ones that are offered before a trial are more familiar to the public. And many advocates are concerned that those deals are fundamentally flawed.

“Scholars have long theorized that plea bargaining has what they call an innocence problem,” Findley said. “The problem is that prosecutors bent on obtaining a conviction have so much discretion and so much power to threaten really onerous sentences, that they can stack up the charges, make the risks of going to trial very, very ominous, and then induce a plea even from an innocent person by making the offer so relatively mild that a rational person would have a hard time rejecting it.”

What concerns Keith Findley about these deals in particular - the ones offered to people litigating a claim of innocence - is he thinks prosecutors are tipping their hand. Findley explained one traditional model of “plea bargaining in the shadow of a trial.” It goes like this. The prosecution and the defense look at the case, the likelihood that they’ll win or lose, and how much time the person might serve - and they split the difference. Eighty percent chance of conviction and a potential 10-year sentence? The prosecutor might offer eight years.

“Now, of course, that's a very simplified model and very simplified description of it,” Findley said. “But that's sort of essentially the theory as to how bargaining works. The reason that that is important is because if you then look at prosecutors in murder cases who are offering plea bargains to time served, that is to zero additional incarceration.”

Findley found in his research that the post-conviction deals offered in these cases were “uniformly steep.” In the great majority, they were for time served. In other words, the defendant would get out of prison immediately.

“What that's suggesting is … when they assess the likelihood of conviction, given the new evidence of innocence, they bargain it all the way down to zero,” Findley said. “That suggests an assessment by the prosecutor that at least in some of these cases, the prosecutor knows the case is incredibly thin. That the chances of conviction are very remote and that, in fact, they may be dealing with an actual innocent person, and yet they proceed to try to preserve the conviction by making this kind of plea offer.”

The problem for the defendant here is the problem Townsend faced. Even if they think they might have a winning case, they’ve already taken their chances with the system once - and lost. For most, as the data shows, the risk is too great. They accept the deals.

“So the system has just beat them down and beat them down and beat them down,” said Julie Jonas with the Great North Innocence Project. “And then a prosecutor says to them, ‘You can leave tomorrow.’ Right? And you're not going to be on probation. You're not going to answer to a probation officer. It will stay on your record. But maybe you have a little criminal record anyhow, right?”

Jonas represented Townsend in his last appeal. She said she’s seen many cases like his, where a prosecutor will let someone out - either with a deal or by deciding not to re-try them - but say publicly that they still believe the person is guilty.

“I think it's prosecutorial face saving,” she said. “You spent time convicting this person. Now, this person went to prison for five years or 10 years. And you're sort of, perhaps you talked to the victims and ... you have lent comfort and solace to them. Right? I think it's very, very hard for a prosecutor to go back and say, ‘You know what? We made a mistake.’ So instead they say, well, we still actually think we were right the first time, but we can't retry him because we don't have the evidence anymore.”

Watch below: KARE 11's 2007 report on Sherman Townsend's release

The ‘why’ behind the deals

Keith Findley said some all-too-human tendencies may make it hard for prosecutors to admit, even to themselves, when the evidence is too thin.

“An ethical prosecutor is not going to prosecute a case in which they believe the person is innocent,” Findley said. “If they're going to offer a plea bargain, they have to say that they believe the person is guilty. Otherwise, it's absolutely inexcusable to be proceeding with a plea offer.”

Findley said it may be that prosecutors “sincerely believe that,” and that belief can be influenced by cognitive biases.

“Things like confirmation bias, which suggests that when an individual reaches a conclusion, they will naturally - this is not a reflection of them as bad people, it's just a reflection that they are people. This is the way people work, right? - When they reach a conclusion, you will naturally seek, remember and interpret all subsequent data in ways that are consistent with your interpretation,” he said. “So it could be that at some level that they recognize the case is remarkably thin, but their cognitive biases are telling them that all of that other evidence of innocence must be weak.”

There’s a related phenomenon called belief perseverance. Once a person forms a conclusion, they will subconsciously undermine evidence that challenges it.

“Even to the point that when a conclusion is reached on the basis of a certain set of facts, and then those facts are demonstrably, unequivocally shown to be false, so that the basis for the conclusion is completely undermined, people will naturally work hard to find other ways to prop up that conclusion,” Findley said.

So what happens when a prosecutor is personally convinced of someone’s guilt - but no longer has the evidence to prove it?

“The way our system works is that until you're convicted, you're entitled to a presumption of innocence,” Findley said. “And the only way that our system can determine whether somebody is guilty or innocent is to go through the process of going through trial and having the prosecutor prove guilt beyond a reasonable doubt, or the defendant waives the trial and pleads guilty.”

Findley said short of that, the person is entitled to a presumption of innocence.

“And so for a prosecutor to publicly say, ‘I believe this person is guilty, but I can't prove it’ is a failure to abide by one of the most basic tenets of our legal system,” Findley said. “And is an unfairness to that person who is just as entitled to the presumption of innocence as you or I.”

Hennepin County Attorney Mike Freeman declined to comment on Townsend’s case or to talk about plea deals for this story.

Ministers of justice

Julie Jonas said that while these plea deals are legal, she does not believe they are ethical when a prosecutor cannot proceed with a new trial.

“Prosecutors under our ethical responsibilities as lawyers are supposed to be ministers of justice,” she said. “And are you acting as a minister of justice if you offer someone a plea deal, knowing that you don't have the evidence going forward? However, I think it happens all the time.”

Jonas said the issues extend to pretrial plea deals as well.

“The prosecutor believes that, you know, knows that they probably at this moment don't have the evidence or really questions their evidence,” she said. “But they also believe that if the person pleads guilty and takes the deal, well, then they are, in fact, guilty. ... And in many cases, they're right. But is that how we want our system to be?”

Of all the people who can answer the question of what Minnesota’s criminal justice system should be, Keith Ellison is one of the most qualified. As the state attorney general, Ellison is essentially Minnesota’s top prosecutor.

“I don't have any quick answers,” Ellison said. “But what I will say is that if I was in prison for a crime that I knew I didn't commit, but somebody said, ‘you say you did, you plead guilty, we'll let you out today.’ And if I had already been away from my family for 12, 13 years and if I was looking at 12, 13, 14 more years to go, would I just say I did it just to get out? I think a lot of people probably would do that. But that undermines the system and undermines the truth.”

Ellison said the solution to the issue may lie with his side of the equation: The prosecutor.

“Those of us who are in a position to prosecute might want to ask, you know. ‘Are we doing this thing the right way?’” he said. “Because some people think, ‘Well, if this guy gets out, it's going to embarrass us.’ And so rather than, we want to avoid the embarrassment of a wrongful conviction and the liability associated with a wrongful conviction and just sort of like, cover it up by hoping that the defendant just takes the deal.”

When asked about whether these deals should be allowed in a post-conviction setting like the ones Keith Findley studied, Ellison said he does not yet have an answer.

“I've been dealing with this for 30 years and I don't know, and I don't have a good answer,” he said. “Because if I'm the defendant facing all that time and you’re telling me the door's open, say the magic words. Do I want that to not be an option?”

Ellison said this is a situation where it is a “heck of a lot easier to stand in judgment than it is to make that decision.”

“We’ve just got to grapple with it,” he said. “Because you might have a prosecutor who says, ‘You know, look, I believe the guy did it. Maybe he's not as culpable as his co-defendants. But I believe he was there. He said he wasn't. I’ll tell you what I'll do. I'll let him out, but he's got to say he did it. Because I believe he did it.’... Should that be not legal to do?”

Ellison said he doesn’t know.

“I know that it's a hard situation and I know that freedom is a precious thing,” he said. “People go to great lengths to get it. And so I guess you're leaving me with the tough questions. I don't have a good answer for them, but I think we need to really dig into it. And we need lawyers and we need community members. We need ethicists. We need all kinds of folks to dig in and help get us to the right answer.”