WAITE PARK, Minn. — In the wee hours at the end of July's special session, legislators passed a new deadly force law that took place March 1.

The new law, based on "preserving the sanctity of every human life," was shaky from the start. It started to live out its uncertain future on Monday when Ramsey County Judge Leonardo Castro hit pause after a lawsuit was filed.

The suit was filed against Governor Tim Walz and the state of Minnesota by four law enforcement groups: the Minnesota Police and Peace Officers Association, Minnesota Chiefs of Police Association, Minnesota Sheriffs Association and Law Enforcement Labor Services.

"What the decision was, was that it was a stay, which means that it stopped the new law from going into effect," attorney Mike Bryant said. "And it said the old law is in effect until the courts are able to look at whether it's constitutional—the new law that was passed."

When asked why the judge would make this decision, Bryant explained the new law's constitutionality is coming into question.

"Judge Castro looked at it and there's a question, the law is being attacked under the constitutionality," Bryant explained. "What the law requires is for police officers to articulate or explain why they used deadly force and under the constitution, you're not required to self-incriminate. What would happen—is there's a conflict, someone would be required to say something that alternatively, the constitution says you never have to do."

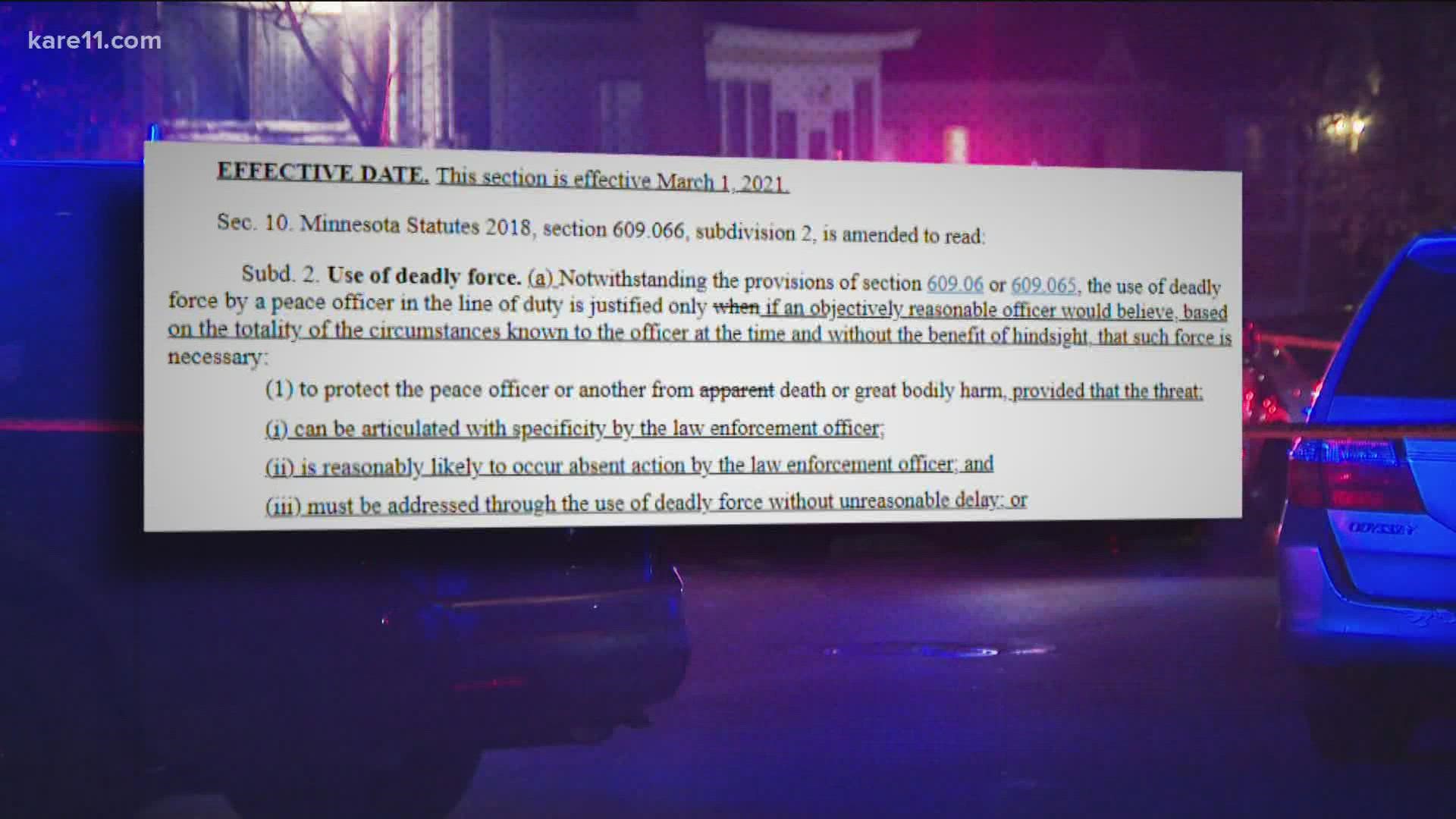

In other words, under the new law, police officers can no longer justify the use of deadly force by claiming that they used it to protect themselves or another person from apparent death or bodily harm.

They must also "articulate with specificity" that the "threat of death or harm is reasonably likely to occur absent action by the law enforcement officer."

"Police officers are given the right to shoot people under what's called the reasonable police officer standard. So we want police officers to protect us, give them the right to shoot people, versus anybody who would shoot somebody. Because of that, they have this extra standard that protects them," Bryant said. "Question is, can they explain why is it that they can use that standard? Police officers do police reports, and all sorts of things that involve them explaining why they did it, but at the same time, requiring them to do that is something against the constitution, and someone can invoke their constitutional right and say 'I'm not going to tell you why I did it.'"

It all boils down to nuance. Bryant said nuances are difficult to navigate, especially when it comes to charges or convictions involving police because rules really weren't written for police at all.

Police officers don't have prior convictions or charges, and they're given a role in which they may need to use deadly force — unlike the average person.

"So when you put all those things together, as scary as it sounds, you may need a standard or a statute that just involves police officers," Bryant said. "Theoretically we'd like to see less of the overall issues come up. None of this really fits in the same way it does with other people that are charged with crimes."

Arguments for the lawsuit will be heard within the next 60 days.