Afraid of what would happen if she was overheard calling police, Wendy Cushing texted 911.

“Hurry please,” she wrote.

She was visibly shaken and had multiple injuries when police arrived. An officer wrote she clutched his arm in constant fear as she was rushed to a hospital.

Once there, she gave police her initial account of what happened: She and her boyfriend were drinking at a friend’s apartment. That drinking turned into arguing; that arguing into yelling. Then he was on top of her, pinning her hips to the ground and wailing on her face with closed fists, she told police according to the report in her case.

Photos documented bruises all over her body, a black eye, a fat lip, and a broken nose. A doctor told her she might need surgery once the swelling subsided, records show.

At the hospital, an officer noticed her phone kept ringing. It was her boyfriend Adam Deyo, the man she said beat her. During one of the calls he blamed her for what happened, according to the police report.

Cushing told police that Deyo, 26, already had domestic violence-related convictions on his record and had been beating her for months.

Police put out an alert that night to arrest Deyo for suspected domestic assault. But they were unable to locate him.

Her story changes

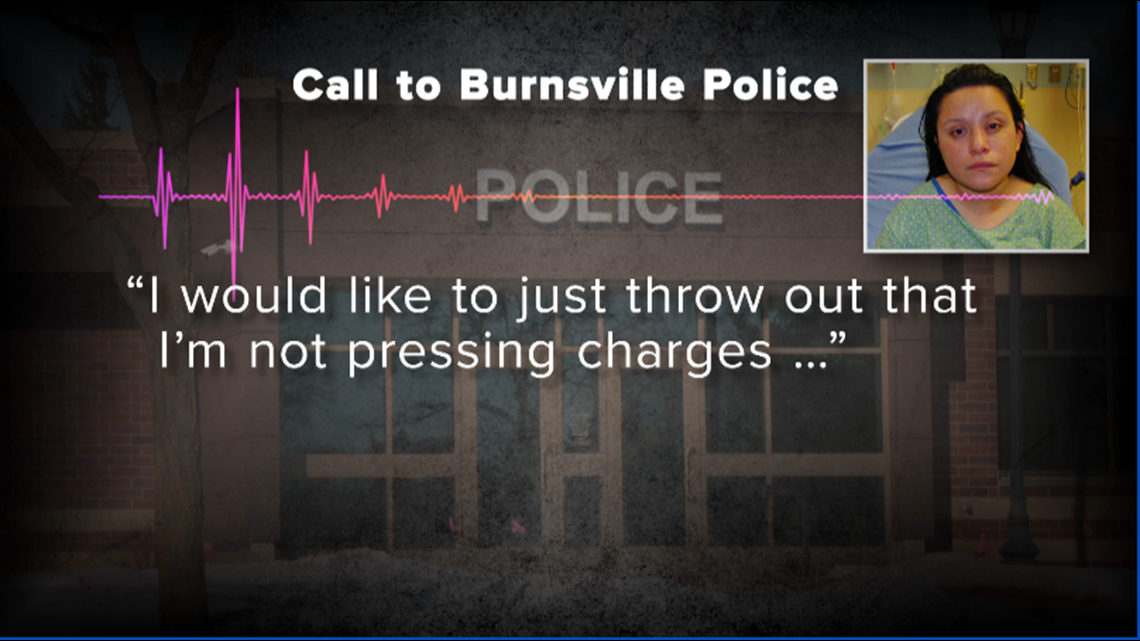

The next day, Cushing called police to recant.

“I would like to just throw out that I’m not pressing charges,” she said in a voice message.

That’s not uncommon. Only around half of domestic assaults are actually reported to police, according to a U.S. Department of Justice Survey. Of those that do report, the Minnesota County Attorneys Association’s own guidelines point out that 85 percent of domestic violence victims recant.

The reason? Fear that the beatings will continue.

“Victims might fear future violence at the hands of this individual or the individual’s family and friends,” said Nikki Engle, the Policy and Legal Systems Program manager at Violence Free Minnesota.

“When a victim is recanting, she is in a highly precarious, dangerous situation,” said Dr. Amy Bonomi, a nationally recognized researcher expert on domestic violence. “Part of the reason she’s trying to protect her abuser is to protect herself from future retaliation.”

When police first tried calling Cushing back, “She stated that she was unable to talk as she was with her boyfriend,” according to an officer’s report.

Experts say the vast majority of recanting victims either blame themselves for their injuries or tell police it never happened.

Wendy Cushing did something else. Records show she blamed another person for the assault. Instead of a fight with her boyfriend, she told police she’d been injured in a jealous fight with another woman.

“I was kind of embarrassed because I had gotten into an altercation with a girl,” she told police. She indicated both women had slept with Deyo.

According to police records, Cushing did not provide investigators with the other woman’s full name – and there’s no indication they ever located her to verify the story.

False report charges

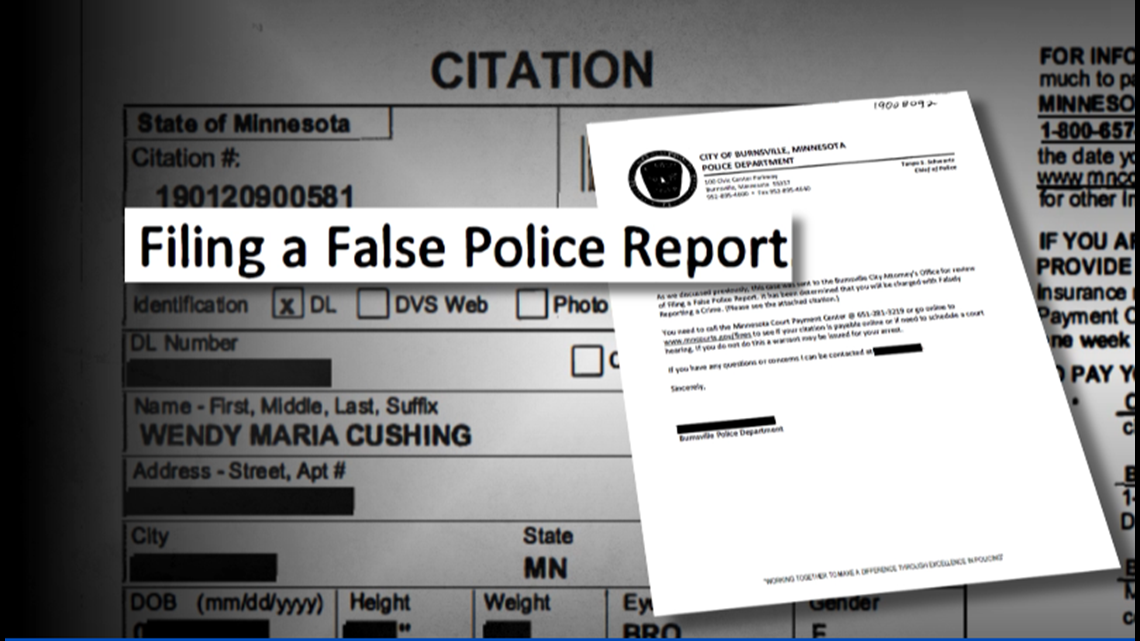

Having told police she was dropping charges against Deyo, Cushing told KARE 11 she thought the situation was behind her. Until a month later – when a criminal citation showed up in the mail.

“I remember getting that initial card – and just looking at it and just crying,” she said.

She was being charged with “Falsely Reporting a Crime.”

“All of a sudden I became the bad guy. Not so much the victim anymore. I became the bad guy,” Cushing told KARE 11.

That charge put her job as a health care worker in jeopardy. A single mother, at stake was her ability to care for her 10-year-old daughter.

Like other abuse victims, Cushing says she changed her story out of fear. “He harassed me over and over until I called the cops,” she said.

After she was treated at the hospital, Cushing says Deyo confronted her – and told her she had to do more than just say she didn’t want to press charges.

Because he had already been convicted of several domestic violence related crimes – and because police had already documented her serious injuries – she said Deyo was worried the case could still be prosecuted even if she claimed the assault never happened.

So, to explain her injuries Cushing needed to blame someone else.

Deyo’s solution? She says he created a cover story, instructing her to tell police that she got into a fight with another woman out of jealousy.

Cushing told KARE 11 she followed Deyo’s instructions. “He orchestrated it,” she said. “He threatened me. What other choice did I have?”

Deyo declined to comment for this story through his attorney.

Victim wrongly charged?

Advocates for victims of domestic assault question whether Cushing should have been charged.

While there are no statistics on how many domestic violence victims who recant are charged with filing a false report, experts interviewed for this story agreed it’s unusual.

Police and prosecutors are generally discouraged from pursuing filing false report charges because even if the victims are lying, the repercussions of charging them could have a chilling effect on reporting future crimes, according to experts and law enforcement interviewed for this story.

“It is very common for a survivor of domestic violence to recant. It is common for a survivor to lie or even testify on the abuser’s behalf,” said Jan Langbein, a co-organizer of the Conference on Crimes Against Women, who reviewed the Cushing case for KARE 11.

After Cushing changed her story, Burnsville police went back to the apartment and spoke with a witness who was there that night, a friend of Deyo’s. While an investigator would write in her report that “he initially claimed he didn’t know much,” he eventually corroborated Cushing’s second story.

Burnsville police dropped the investigation against Deyo, then sent the case to the Burnsville City Prosecutor to review whether Cushing should be accused of filing a false report.

The prosecutor, Elliott Knetsch, decided to press charges, believing that there had been a fight between the women – not with Deyo.

Knetsch said it was only the second time in his 35-year career that he’s filed charges against a domestic violence victim who recanted. The first time was someone more than 20 years ago, he said, when the person repeatedly made accusations against the same person but recanted each time.

Cushing’s case was even different from that.

“I don’t even look at it as a case of recanting,” Knetsch said. Instead, he said he saw it as a case of Deyo being falsely accused of a crime.

The evidence he cites: Deyo being overheard telling Cushing it was her fault the night she was in the hospital, her second statement to police and the witness corroboration.

“The fact is that it was another girl that beat her up,” Knetsch said.

Flawed investigation

There were problems with the case against Cushing, KARE 11 Investigates has discovered.

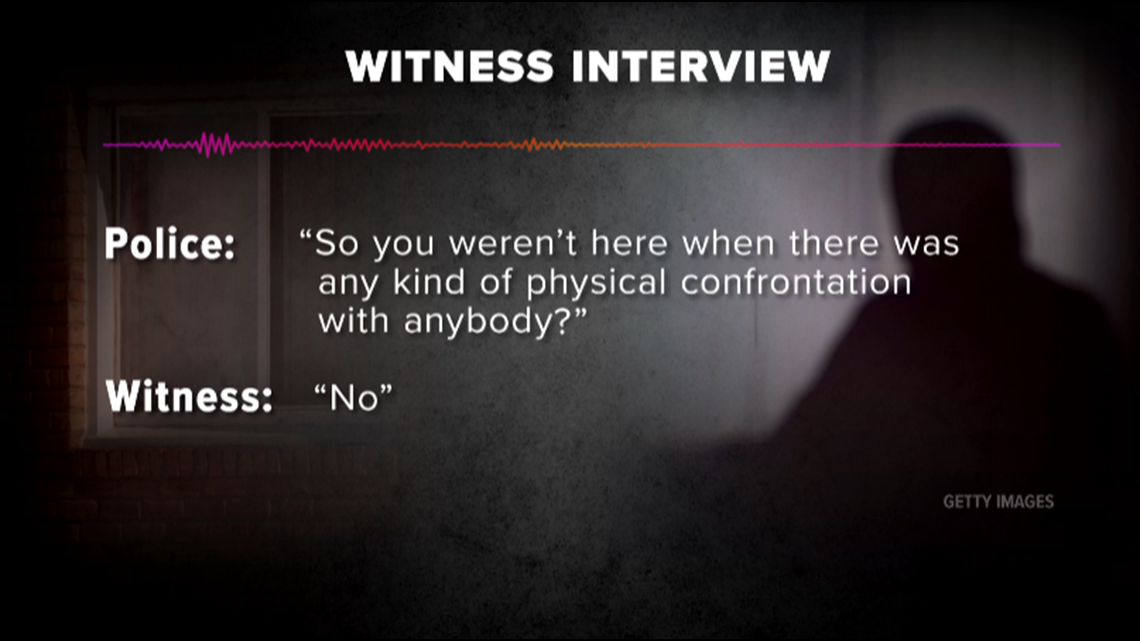

For starters, records show the witness at the apartment that night initially lied to police. KARE 11 obtained a copy of the recording, showing he first denied even knowing who was at his apartment, then denied witnessing a fight.

“So, you weren’t here when there was any kind of physical confrontation with anyone?” an officer asked.

“No,” he answered.

He also claimed to have left the apartment to go to a local convenience store. When a police officer threatened to pull the store’s surveillance video to verify his story, he acknowledged he wasn’t telling the truth.

By the time the witness changed his story, the police officers had already asked if there had been a fight between the two women – even telling him the first name of the woman who allegedly assaulted Cushing.

“So did the girls get in a physical fight?” an officer asked. “A little bit, yeah,” Deyo’s friend finally responded.

Knetsch said he never listened to the audio recording of that interview.

Police closed their investigation without speaking to Deyo – or the woman who supposedly fought with Cushing.

“I’d want to bring these people in for an interview,” said Mark Wynn, a former Lieutenant with the Nashville Police Department who now trains law enforcement across the country on how to investigate domestic assault. He reviewed the Cushing case files for KARE 11.

Instead of charging Wendy, Wynn says police should have continued to investigate to determine if Deyo was not only responsible for abusing her, but also for witness tampering.

“I would recommend to them to open this case back up and not call it inactive,” Wynn said. “We know these crimes don’t stop. They go on and on and on which means we have a responsibility to try to determine how dangerous they are.”

“I think the police lost their focus,” said Langbein of the Conference on Crimes Against Women. “They shouldn’t be looking at a crime she committed, they should be looking at the crimes committed against her.”

Burnsville Police Chief Tanya Schwartz would not make herself available for an interview, but in a statement the department said it stood by Knetsch’s decision to charge Cushing.

Unlike the prosecutor and police, KARE 11 found the woman who supposedly fought with Cushing.

She said she didn’t even know Cushing. She denied being at the apartment that night. And she said she didn’t know her name was used in connection with an assault.

“I had just had a baby at that time,” she told KARE 11.

More harassment

Even though Cushing recanted, she says that didn’t stop Deyo from harassing her.

Six months after the incident at the apartment, she applied for an Order for Protection against him, detailing the December assault along with what she said was months of abuse.

In June, a judge issued an order barring Deyo from contacting her.

Despite the order, one night last September Deyo went to her apartment, smashed the front window and pounded on her door, according to a criminal complaint in the case.

Cushing feared he would only continue, so she let him in, only to have him punch her in the face three times with a closed fist, the complaint said.

Hennepin County prosecutors charged Deyo with felony domestic assault and violating the protective order.

He accepted a deal on Dec. 22, pleading guilty to violating the protection order in exchange for three years of probation and 30 days in jail.

Charges finally dropped

Last month, as KARE 11 began investigating this case, Knetsch dropped the charge against Cushing. The Burnsville prosecutor said he hadn’t known about the subsequent felony charges against Deyo.

That still meant for a year Wendy lived with the fear of what a criminal record would mean for her and her daughter.

Now that the struggle is over, she said she’s speaking out, hoping that what happened to her never happens to anyone else.

“The justice system is a place that is supposed to protect you,” she said. “I didn’t ask to get hurt. I didn’t ask to get beaten. I didn’t ask for any of those things.”

If you are a victim of domestic violence, call the domestic abuse hotline toll-free at 866-223-1111.